Mutinus caninus (Huds.) Fr. - Dog Stinkhorn

Phylum: Basidiomycota - Class: Agaricomycetes - Order: Phallales - Family: Phallaceae

Distribution - Taxonomic History - Etymology -Identification - Culinary Notes - Reference Sources

Mutinus caninus, the Dog Stinkhorn, is harder to find than the Common Stinkhorn, Phallus impudicus, because it is rather less smelly and much less widespread in its distribution. This is also a much smaller fruitbody.

The many kinds of stinkhorn fungi that occur worldwide, plus various puffballs, earthballs, earthstars, stiltballs and the like have long been grouped together in an entirely artificial taxonomic - Class, the gasteromycetes.

Stinkhorns depend entirely on insects for their reproduction. When (mainly diptera) flies are attracted to the smell (of rotting meat) of the gleba on the tips of the fruitbodies, some of the spore-laden gleba sticks to the insects' feet and is eventually transported to dead wood in other locations. As flies visit several stinkhorns so the necessary spore diversity is achieved - in a mannervery much like pollination of flowers by insects - and so a new fertile mycelium can develop on a suitable growing substrate.

Distribution

Uncommon but far from rare, the Dog Stinkhorn is widely distributed throughout Britain and Ireland. Mutinus caninus also occurs in most parts of mainland Europe from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean region. (The specimen shown below was found in southern Portugal.) This species, together with several other similar fungi, is also found in North America.

Taxonomic history

In 1778 British botanist William Hudson (1730 - 1793) described this species scientifically and gave it the name Phallus caninus. It was the great Swedish mycologist Elias Magnus Fries who, in splitting the genus Phallus in 1849, transferred the Dog Stinkhorn to the new genus Mutinus, thus establishing the currently accepted name of this species as Mutinus caninus.

Synonyms of Mutinus caninus include Phallus caninus Huds., Phallus inodorus Sowerby, Ithyphallus inodorus Gray, and Cynophallus caninus (Huds.) Berk.

Etymology

The genus name Mutinus comes from Latin and means a penis, while - just as it sounds - the specific epithet caninus is a canine allusion, making the binomial name a reference to dogs' phallic bits! (the term Dog in botanical common English such as Dog Violet means 'common'; however, it can hardly be argued that this is the case with Mutinus caninus, which according to official records in Britain and Ireland is much less common than its larger relative of similar shape the Stinkhorn Phallus impudicus.)

Identification guide

|

DescriptionThe 'egg' from which the Dog Stinkhorn develops is usually almost completely buried and difficult to find until the stipe emerges from the egg - unlike the Common Stinkhorn, Phallus impudicus, whose eggs develop with much more exposed above ground. Typically 8 to 15cm tall; stipe diameter is 1 to 1.5cm. The cap is honeycombed beneath the gleba (a shiny, sticky, smelly coating that contains the spores). Once insects have consumed the dark olive gleba, the tip of the fungus turns orange and then the whole fruitbody decays rapidly: there is usually nothing left within three or four days. |

|

VolvaThe volva-like remains of the 'egg' often appear above the ground once the fruitbody is fully developed. StemThe white stipe has a texture and appearance of expanded polystyrene and is barely strong enough to support the small, half-egg-shaped head with its coating of sticky olive gleba. |

|

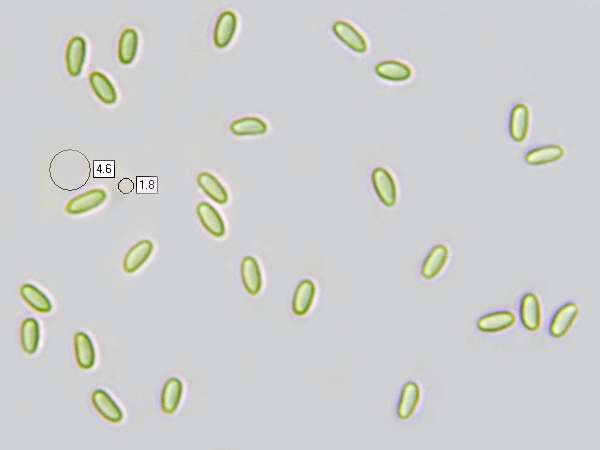

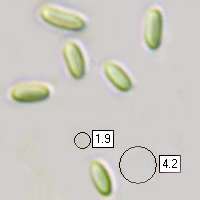

SporesOblong, smooth, 4-5 x 1.5-2µm.

Spore printThe gleba, which is dark olive, contains pale yellow spores. |

Odour/taste |

Unpleasant odour, but not as strong as that of the Common Stinkhorn, Phallus impudicus. I haven't found anyone with experience of tasting Dog Stinkhorns! |

Habitat |

Saprobic, found growing in small groups and sometimes in fairy rings, most often in coniferous forests and close to rotting stumps of other sources of well-rotted timber. These fungi sometimes fruit on damp old woodchip mulch in parks and gardens. |

Season |

July to early October in Britain and Ireland. |

Similar species |

Phallus impudicus, the Common Stinkhorn, is much larger and has a stronger odour; its honeycombed cap surface is white rather than orange beneath the gleba. |

Culinary notes

The smell of a mature Dog Stinkhorn is nowhere near as strong as the vile odours of many other members (sic!) of the stinkhorn family. The immature eggs of this gasteromycete fungus are stated in some field guides to be edible but in others inedible.

Although they are not known to be seriously poisonous, these are definitely not delectable fungi. Several people have reported their dogs being very sick after eating mature Dog Stinkhorns, and so it's most likely that any person eating mature specimens would suffer a similar fate. In China the dried eggs of Dog Stinkhorn are readily available in shops and, it seems, they are quite popular as edible fungi - but maybe the big attraction is their assumed medicinal value. Now I wonder what that might be? Unfortunately we can't ask the flies that have eaten the gleba from the specimen shown below...

Reference Sources

Fascinated by Fungi, 2nd Edition, Pat O'Reilly 2016, reprinted by Coch-y-bonddu Books in 2022.

Pegler, D.N., Laessoe, T. & Spooner, B.M (1995). British Puffballs, Earthstars and Stinkhorns. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Dictionary of the Fungi; Paul M. Kirk, Paul F. Cannon, David W. Minter and J. A. Stalpers; CABI, 2008

Taxonomic history and synonym information on these pages is drawn from many sources but in particular from the British Mycological Society's GB Checklist of Fungi.

Acknowledgements

This page includes pictures kindly contributed by Simon Harding and David Kelly.

Fascinated by Fungi. Back by popular demand, Pat O'Reilly's best-selling 450-page hardback book is available now. The latest second edition was republished with a sparkling new cover design in September 2022 by Coch-y-Bonddu Books. Full details and copies are available from the publisher's online bookshop...