Polyporus squamosus (Huds.) Fr. - Dryad's Saddle

Phylum: Basidiomycota - Class: Agaricomycetes - Order: Polyporales - Family: Polyporaceae

Distribution - Taxonomic History - Etymology - Identification - Culinary Notes - Reference Sources

Polyporus squamosus, commonly referred to as Dryad's Saddle, grows in overlapping clusters and tiers on broad-leaved trees. (A dryad is a mythical wood-nymph.) The fruit bodies appear in summer and autumn. Insects quickly devour these large brackets, and in warm weather they can decay from full splendour to almost nothing in just a few days.

Sycamore, willow, poplar and walnut trees are all commonly attacked by this impressively large and attractive fungus

.

When growing on the trunks of trees this polypore forms brackets that do look rather like saddles; however, they can also occur on fallen trunks and large branches or emerge from the soil where a tree root is just below soil level. In these situations Polyporus squamosus takes on a very different form: a funnel. Some of these funnels are perfect horns; more often they are slightly one sided.

The beautiful funnel-shaped Dryad's Saddles shown above were found in woodland in Wales quite early in the season - even for what is one of the earliest of the annual bracket fungi.

The outer edges of young caps are edible and tender, but mature caps have tough flesh - especially near to the attachment point. Within three or four weeks, Dryad's Saddles become maggot ridden and turn into a smelly mess.

Distribution

Polyporus squamosus is one of the most common of the bracket fungi seen in Britain and Ireland. It occurs across most of mainland Europe and in many parts of Asia and North America.

Taxonomic history

First described scientifically in 1778 by English botanist and apothecary William Hudson (~1730 - 1793), who named it Boletus squamosus, this species was renamed Polyporus squamosus by the great Swedish mycologist Elias Magnus Fries in his Systema Mycologicum of 1821.

Synonyms of Polyporus squamosus include Boletus squamosus Huds., and Cerioporus squamosus (Huds.) Quel.

Etymology

The generic name Polyporus means 'having many pores', and fungi in this genus do indeed have tubes terminating in pores (usually very small and a lot of them) rather than gills or any other kind of hymenial surface.

The specific epithet squamosus means scaly, and in the case of the Dryad's Saddle the cap surface is indeed beautifully patterned with large brown scales.

With the increasing incidence of Ash Die-back disease, it can be expected that Dryad's Saddles become an even more common sight. Often when an old tree becomes infected with this fungus the fruitbodies emerge well above head height, as was the case with the fruitbodies pictured immediately above, which emerged from the trunk more than four metres above ground level.

The huge Dryad's Saddle brackets shown above were up to 50cm in diameter. They were photographed in late May 2014 (hence the Bluebells) in West Wales, and the host tree was an Ash that was suffering from die-back disease.

Identification guide

|

CapIndividual caps grow to between 10 and 60cm in diameter and are 5 to 50mm thick. Often in tiers, the caps are attached to the host tree by a very short lateral (occasionally eccentric but not quite lateral) stem that darkens towards the base. Beneath the yellow to tan upper surface, the cap flesh is white and tough. |

|

Tubes and PoresIrregularly oval tubes 5 to 10mm deep terminate in irregular, angular pores that are white at first but turn cream as the fruiting body matures. The tubes run decurrently on to the short stem. |

|

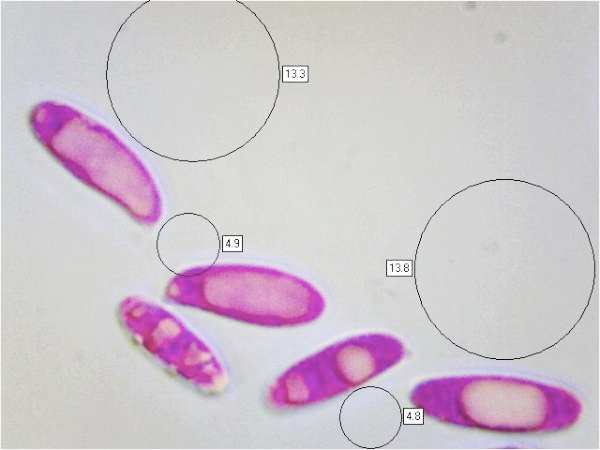

SporesOblong-ellipsoidal, smooth, 10-15 x 4-5.5µm.

Spore printWhite. |

Odour/taste |

Floury odour and taste. |

Habitat & Ecological role |

Parasitic and later saprobic on broad-leaf trees. |

Season |

Spring to late summer or early autumn. |

Similar species |

Piptoporus betulinus, the Razor Strop Fungus or Birch Polypore, is a similar shape when fully mature, but it is brown on top and white underneath; it is specific to birch trees. |

Culinary Notes

I have come across recipes in which slices of young Dryad's Saddles are fried with bacon and served on hot buttered toast, but I have no first-hand experience of trying these mushrooms. In any case use only young caps, slice them thinly to check that they are maggot free, and cook them thoroughly.

Although the tiered brackets of Dryad's Saddle on this old Sycamore tree (above) near Bala, North Wales, would provide a bountiful harvest, at this stage the pore surfaces are darkening and the brackets are now too tough to be worth gathering for human consumption. They will not be wasted, however, because tiny dipteran insects known as 'fungus flies' will find them and burrow into the pores to lay their eggs; within a few days maggots hatch and quickly consume the decaying fungi.

Reference Sources

Mattheck, C., and Weber, K. (2003). Manual of Wood Decays in Trees. Arboricultural Association

Pat O'Reilly (2016). Fascinated by Fungi, First Nature Publishing

BMS List of English Names for Fungi

Paul M. Kirk, Paul F. Cannon, David W. Minter and J. A. Stalpers. (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi; CABI.

Taxonomic history and synonym information on these pages is drawn from many sources but in particular from the British Mycological Society's GB Checklist of Fungi.

Acknowledgements

This page includes pictures kindly contributed by Chris and Rachel Barnes, and Simon Harding.

Fascinated by Fungi. Back by popular demand, Pat O'Reilly's best-selling 450-page hardback book is available now. The latest second edition was republished with a sparkling new cover design in September 2022 by Coch-y-Bonddu Books. Full details and copies are available from the publisher's online bookshop...