Boletus edulis Bull. - Cep, Porcini or Penny Bun Bolete

Phylum: Basidiomycota - Class: Agaricomycetes - Order: Boletales - Family: Boletaceae

Distribution - Taxonomic History - Etymology - Identification - Culinary Notes - Reference Sources

Boletus edulis, known as the Cep, Porcino or Penny-bun Bolete, is a most sought-after edible bolete. It is frequently found at the edges of clearings in broad-leaved and coniferous forests.

Most boletes, and certainly all of the common ones found in Britain and Ireland, are ectomycorrhizal fungi. This means that they form mutualistic relationships with the root systems of certain kinds but of trees and/or shrubs (usually with one or more plant genera).

In this kind of symbiotic relationship the fungi help the tree to obtain vital minerals from the soil, and in return the root system of the tree delivers energy-rich nutrients, the products of photosynthesis, to the fungal mycelium. Although most trees can survive without their mycorrhizal partners, boletes (and many other kinds of forest-floor fungi) cannot survive without trees; consequently these so-called 'obligately mycorrhizal' fungi do not occur in open grassland. (The roots of trees extend a long way, however, and so you could find Ceps springing up some tens of metres away from the trunk of its partner tree.)

If you want to improve your chances of finding Ceps, it helps a great deal if you look in the right kinds of places and under the trees that these magnificent mushrooms are most commonly linked to. There is a lot more information on this topic, including chapters detailing which fungi species are obligately mycorrhizal and the kinds of tree each is associated with, in Fascinated by Fungi.

Distribution

Fairly frequent throughout Britain and Ireland as well as on mainland Europe and in Asia, Boletus edulis also occurs in the USA, where it is known as the King Bolete, although it is a matter of ongoing debate whether the American mushroom is in fact the same species as that found in Europe. Boletus edulis has been introduced to southern Africa as well as to Australia and New Zealand.

The tubby-stemmed Cep shown above was found in heathland habitat in the Caledonian Forest near Aviemore, in central Scotland. There conifers are the dominant trees, but plenty of self-seeded birches grow beside forest tracks.

There are many tales in folklore about the best times to hunt for Ceps, and a full moon is commonly cited as auspicious; we doubt that very much! A few days after summer rain is often, in our experience, when the young, fresh fruitbodies are at their very best. Leave it a week to ten days and more of the Ceps that you find are likely to contain maggots. When its gills have turned greenish yellow a Cep is very likely indeed to be maggoty. (Some people simply remove the maggots and then use these middle-aged mushrooms in their cooking!)

Taxonomic history

This bolete was first described in 1782 by French botanist Jean Baptiste Francois (often referred to as Pierre) Bulliard, and the specific name and genus remain unchanged today, so that Boletus edulis Bull. is still its formal scientific name under the current rules of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN). Boletus edulis is the type species of the genus Boletus.

Etymology

The generic name Boletus comes from the Greek bolos, meaning 'lump of clay', while the specific epithet edulis means 'edible' - in this instance the mushroom is indeed good to eat, but beware: at least one specific epithet meaning edible has been attached to a poisonous fungus species: Gyromitra esculenta.

Identification guide

|

CapWith a slightly greasy penny-bun-like surface texture, the yellow-brown to reddish-brown caps of Boletus edulis range from 10 to 30cm diameter at maturity. (An exceptionally large cap can weigh more than 1kg, with a stem of similar weight.) The margin is usually a lighter colour than the rest of the cap; and when cut, the cap flesh remains white, with no hint of blueing. |

|

Tubes and PoresThe tubes (seen when the cap is broken or sliced) are pale yellow or olive-brown and are easily removed from the cap; they end in very small white or yellowish pores. When cut or bruised, the pores and tubes of Boletus edulis do not change colour (as the pores of some otherwise quite similar species do). |

|

StemA faint white net pattern (reticulum) is generally visible on the cream background of the stem, most noticeably near the apex. Clavate (club-shaped) or barrel-shaped, the stem of a Cep is 10 to 20cm tall and up to 10cm in diameter at its widest point. The stem flesh is white and solid. |

|

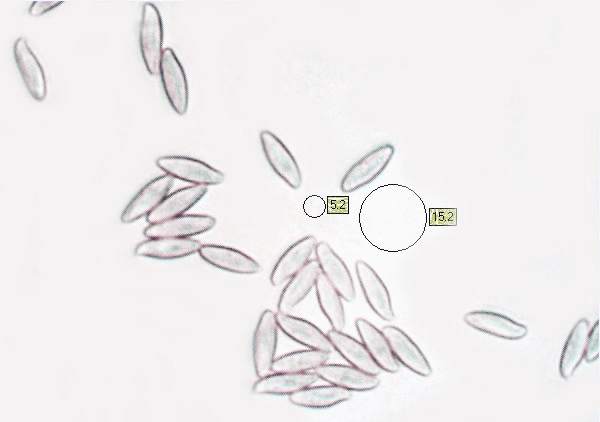

SporesSubfusiform, smooth, 14-17 x 5-7μm.

Spore printOlive-brown. |

Odour/taste |

Boletus edulis has a faint but pleasant smell and a mild nutty taste. |

Habitat & Ecological role |

Boletus edulis grows on soil beneath trees, notably beech and birch, and less commonly oaks as well as pines, spruces and occasionally other conifers. In southern Europe this species is found in scrubland domonated by Cistus ladanifer and other rock rose species. |

Season |

June to October in Britain and Ireland. |

Similar species |

Tylopilus felleus has a darker stem and pinkish tinge to its pores; it has a very bitter taste. |

Culinary Notes

Boletus edulis is one of the finest edible mushrooms. Although it can be used in any recipe calling for cultivated (button) mushrooms, there are some dishes in which it truly excels. It is great in rissotto dishes and omelettes, and it certainly has enough flavour to make tasty sauces to be served with meat dishes. Do give our Penny Bun Starter a try; we think you will love it!

When gathering these mushrooms for the table, those that are fully developed but still young are best of all. Caps can be very large (up to 30cm across), and so a family feast requires very few of these mushrooms - indeed, one large Cep is quite enough for a risotto for four people.

One of the reasons that Boletus edulis is considered to be such a safe mushroom to collect for the table is that none of its close lookalikes is poisonous. Provided you avoid boletes with red or pink pores you will at least be assured of a passable meal, and if you ensure that Boletus edulis dominates in the ingredients then your mushroom meal will be acclaimed as at least very good if not truly outstanding. For example boletoid fungi such as Leccinum scabrum, the Brown Birch Bolete, can be used to bulk up a cep recipe with both safety and confidence that it will taste pretty good.

Boletus edulis tastes great when fresh; it is also one of the very finest fungi for drying or freezing. We dry our Ceps, as the flavour is certainly not degraded by the process and many people tell us that they find dried Ceps even more tasty than fresh ones. To dry these mushrooms, cut them into thin slices and either place them on a warm radiator or in a warm oven (with its door open to let the moist air escape).

In the book Fascinated by Fungi (see the sidebar on this page for brief details and a link to full information, reviews etc) there is a good selection of magnificent mushroom menus all based on our 'Magnificent Seven', and Boletus edulis is, of course, one of the seven. After truffles, Ceps (although going by various common names depending on the country, culture and sometimes even the locality) are surely the most highly prized of edible fungi in Europe and the USA, where the name King Bolete is given to Boletus edulis.

In France these chunky edible fungi go by the nickname Bouchon, meaning cork, but more commonly French people refer to them as either cepes or, more formally, cèpes - the accent on the first e is omitted on most websites, however. When in Sweden, I have to remember to refer to this mushroom as Karljohan svamp. In Scandinavia this mushroom is named after Carl XIV of Sweden and John III of Norway (1763 - 1818), who despite being born a Frenchman (Jean Bernadotte) was elected, in 1818, to become king of a united Sweden and Norway when the Swedish royal family had no succession. Why the link to one of the world's finest edible fungi? Simple: he liked them a lot - so much, in fact, that he even tried to cultivate these prized edible fungi in the park grounds of the royal palace, but it seems without success. (Ectomycorrhizal fungi such as Boletus edulis are in general very much more difficult to cultivate than saprophytic fungi.)

Reference Sources

Fascinated by Fungi, 2nd Edition, Pat O'Reilly 2016, reprinted by Coch-y-bonddu Books in 2022.

British Boletes, with keys to species, Geoffrey Kibby (self published) 3rd Edition 2012

Roy Watling & Hills, A.E. 2005. Boletes and their allies (revised and enlarged edition), - in: Henderson, D.M., Orton, P.D. & Watling, R. [eds]. British Fungus Flora. Agarics and boleti. Vol. 1. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

Dictionary of the Fungi; Paul M. Kirk, Paul F. Cannon, David W. Minter and J. A. Stalpers; CABI, 2008

Taxonomic history and synonym information on these pages is drawn from many sources but in particular from the British Mycological Society's GB Checklist of Fungi.

Acknowledgements

This page includes pictures kindly contributed by David Kelly.

Fascinated by Fungi. Back by popular demand, Pat O'Reilly's best-selling 450-page hardback book is available now. The latest second edition was republished with a sparkling new cover design in September 2022 by Coch-y-Bonddu Books. Full details and copies are available from the publisher's online bookshop...